- Home

- Francine Mathews

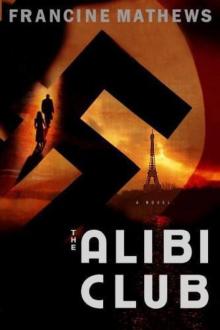

The Alibi Club

The Alibi Club Read online

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

MAP

PROLOGUE

AMERICAN BUSINESS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

FRENCH INTRIGUE

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

BRITISH EFFICIENCY

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE

AFTERWORD

EPILOGUE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BY FRANCINE MATHEWS

COPYRIGHT PAGE

This book is for Kate Miciak,

with thanks

for all the brilliant years

PROLOGUE

March 12, 1940

There were nine people waiting in the stuffy room that faced the aerodrome’s tarmac, ten if you counted the sleeping child swaddled in a blanket in the Italian girl’s arms. Three women, six men, several nationalities, and the brazen churn of propellers beyond the frosted window. Each of the waiting passengers was desperate enough to leave Oslo in the dead of night and dead of winter, so the air hummed with suppressed violence and restlessness and incipient hysteria. No one spoke.

Jacques Allier had his back to the wall nearest the door, an evening newspaper grasped in one gloved hand, the other thrust in his pocket. The unheated room was freezing, but his skin was beaded with sweat and his hidden fingers clutched a gun.

The clock read three minutes until midnight. The plane would leave at 12:07. Allier’s passport had been taken ten minutes ago and not returned. The man named Demars—who had all his luggage—was inexplicably missing from the aerodrome, and this was only one of the factors contributing to Allier’s sweat. He hated to fly. When he’d undertaken this operation he’d asked for a submarine out of Brest. A destroyer from Tønsberg. He’d gotten an eight-seater with ice on its wings and no guns to speak of.

He was praying he’d be allowed to board, although Allier was one of those who could not believe in God. Not now.

He was a spare, bland-faced man in the good cloth coat and spectacles of a banker, mid-forties perhaps, clearly European but shockingly unmilitary for the times. His eyes drifted away from the damning clock—the man Demars was still missing—and roved indifferently over the faces of his fellow passengers. Two men arguing politics in Dutch. A gawky boy in his teens, his looks feverish and his hands drumming nervously against the arm of his chair, fingers spilling cigarette ash onto the linoleum floor. A gray-haired woman stolidly eating pickled herring from a waxed paper box furnished by an Oslo shop. None of them spoke. None made eye contact. Only the tall, burly blond fellow in the impeccable camel-hair coat was staring openly, a slight smile curving his lips, at the Italian girl with the sleeping child.

And who could blame him? Allier thought irritably. She was exquisite, with her fur collar grazing her faintly flushed cheek, her dark knot of hair shining beneath the arc of her hat. Her fingers were gloved in ostrich skin; the frail hunch of her shoulders might reflect the penetrating cold, or the solicitude that kept her bent, Madonna-like, over the face of her infant. Was she even twenty? Her passport and ticket lay on the hard wooden bench beside her; like Allier, she was bound for Amsterdam in the dead of night.

Turn back, he urged. Go north. Go west. Go anywhere but home. He had caught one glimpse of her mouth, curved like a G clef, and her eyes, disconcertingly blue in an olive-skinned face. The blond hero opposite had glimpsed them, too.

“Madam,” the man said gently in Italian, “you look chilled to the bone. Perhaps a cigarette?…If I were to light it for you…?”

The girl ignored him, failing to so much as lift her head. Allier exulted in this, in the snub offered the blond hero who might from his looks have been Norwegian or even English but who Allier knew now was German—a broad-shouldered, perfect German in civilian dress lounging in the very aerodrome where he, Allier, had elected to escape. This could not be coincidence; this was part of a plan. The fact of the German presence meant that Allier was already a dead man. Demars and the luggage would not be coming.

He tossed the folded newspaper into a waste bin and moved casually toward the door leading out to the planes. One of them bound for Perth, the other for Amsterdam. The propellers whined in the cold, the pilots worried about ice. It was possible that they would all be told to go home—to try again tomorrow—and for Allier there would be the certainty of an armed escort at some point along his route back to the French legation, a sudden flurried movement into an enemy car, a bullet in the temple after how many agonizing hours of interrogation? He continued to stare through the waiting-room window, his gloved hands clasped behind his back. Conscious of movement. Some kind of rank closing behind.

It was barely two weeks since he’d vaulted up the marble steps of the Armaments Ministry and accepted the fake passport in his mother’s maiden name. Freiss. He was Michel Freiss of Salzburg, aged forty-one, a banker with no interest in this phony war between France and the Germans that had been going on for seven months now without a shot fired. That night he’d taken the last train across the border, bound for Amsterdam, and then by slow degrees traveled north to Stockholm and finally Oslo. There were five days of negotiation in a tiny snowbound town near the Telemark mountains, ponderous dinners and pledges of eternal friendship and risky flourishes of the French flag. Oblique counsels in the legation, none of the usual diplomats in on the secret, and the lights burning all night in the German intelligence pavilion across the garden wall.

“You’re famous,” the French ambassador assured him with a twisted smile. “Everybody wants to talk to you. Our people caught this the day you left Paris.”

It was a decoded German radio transmission he carelessly handed Allier: At any price intercept a suspect Frenchman traveling under the name of Freiss. What the ambassador had not bothered to point out was that Allier had been betrayed before he’d boarded the night train to Amsterdam.

Who? he asked himself now. A spy in Dautry’s office? Somebody at the bank?

The two-beat note of a police siren was audible, suddenly, in the distance; insistent, rising, certainly closer.

Perhaps it was the lab. One of Joliot’s people. Or fucking Demars. He’s probably sold the luggage.

“Mr. Freiss,” said a voice at his elbow.

He turned, caught the untroubled face of Norwegian Border Control. A woman, neatly uniformed. Her clipped hair so fair it might almost be white. She was offering him a bunch of papers, but he ignored her extended ha

nd. The police sirens had pulled up to the aerodrome door. The butt of his gun twisted in his fingers, slippery with sweat. In a matter of seconds the door would burst open, a clutch of men tripping over themselves in their haste to seize him. He might have time to take one of them down—the big German, perhaps—but there were these women, that child in the Madonna’s arms…

“Your passport and ticket for Amsterdam,” Border Control persisted. “Everything is in order. You may proceed to the tarmac.”

He glanced over her head and met the German’s eyes. The man was still smiling faintly, the same indulgent look he’d turned on the young Italian princess, who was rising now from her seat, magnificent and indifferent. He’s let me run all this way so he could follow my trail, Allier thought. I’ll lead him no further.

He took his passport and ticket from the woman’s hand and without a word held the door wide. The Italian girl flicked him one glance from her arresting blue eyes as she passed; not even this, Allier thought, was comfort before dying. Then he and the blond hero followed her into the cold.

There was confusion about the planes: A huge black Daimler had driven straight onto the tarmac and thrust itself between them. A man was running distractedly beneath the wings, shouting inaudibly over the clatter of the engines and barely avoiding the propellers. His driver pulled an astonishing number of suitcases from the idling car. The police and their sirens were silent now, beyond the runway gates; it was the Daimler they had escorted through the streets of Oslo, wailing right up to the Amsterdam flight. Allier felt his face flush with heat and his hands clench: This is what hope feels like. Terror and a clenched fist. He recognized the dapper, black-haired figure pirouetting beneath the fuselage; he recognized the suitcases. Demars’s driver was loading them even now into the belly of the Perth plane.

Allier counted them as best he could across the distance and darkness. Thirteen, he thought. Please God let there be thirteen.

Demars collided headlong with the German’s camel-hair coat; whiskey fumes and cigar smoke wafted through the frigid night air.

“Pardon, most esteemed sir.” He spoke Norwegian and he clutched the German’s sleeve like a spoiled child. “Which of these is the Amsterdam plane? Have I missed it? I must at all costs make the Amsterdam plane!”

They argued the destination of both flights, the Daimler’s right to park in the middle of the tarmac, the abuse of police escort, the advisability of arriving on time. Allier kept walking. He did not look back. The Italian girl boarded the Amsterdam plane with a grimace on her face, the saintly infant now screaming in her arms. Allier’s ticket fluttered to the ground. He pulled a second one—stamped for Perth—from his breast pocket.

As the Amsterdam pilot taxied toward his takeoff, Allier caught a glimpse of the blond German under the tarmac lights: hatless, his coat flying back like wings, running hopelessly after the wrong plane.

Fog diverted them. As was expected.

They landed near dawn in a town Allier had never heard of, somewhere on the east coast of Scotland. A small field, quite deserted, the waiting-room windows blacked out with painted canvas. The pilot gave him tea. From politeness he tried to drink it.

“Did you hear?” the man asked him. “The Germans shot down that plane. The one bound for Amsterdam last night.”

Allier thought of the young Italian girl, the two men arguing in Dutch, the child that would have been wailing, certainly, as the flames bloomed in the cockpit and the frantic pilot beat them back. The long tight fall into the North Sea, implacable as a destroyer’s hull.

He set down the tea.

“What have you got in all those suitcases?” the pilot asked curiously. “The crown jewels of Norway?”

Allier glanced at the man. The truth was a breach of security but the pilot would never believe him, anyway.

“Water,” he replied.

CHAPTER ONE

Later, they would remember that spring as one of the most glorious they’d ever known in Paris. The flowering of pleached fruit trees and the scent of lime blossom crushed underfoot, the chestnuts unfurling their leaves in ordered ranks along the Champs-Élysées, the women’s silks rustling like wings as they hurried to dinner—all had a perilous sweetness, like absinthe. Sally King, who had lived in the city for nearly three years now and might be acknowledged as something of an expert, maintained that even when it rained Paris was ravishing. The streets shone in the sudden torrents regardless of grime or automobile petrol or the piss in the open urinals; they glistened with a brilliance that was consumptive and suicidal.

She was surging against the tide of people on the Pont Neuf that night, across the narrowest point of the little island that sat like a raft in the middle of the Seine, having already fought her way past the shuttered bookstalls of the Quai de la Tournelle. She did not move swiftly, because the French heels of her evening sandals caught in the cracks between the paving stones. It was dark, blackout dark, and she would have liked a taxi but there were none to be found. She could sense the panic in the hunched shoulders and too-rapid steps of the Parisians, some of whom turned despite their fear and stared at her openly: Sally King, tall and angular, all her beauty in the impossible length of her legs, the clarity of her frame beneath the candy-wrapper gown.

She had been living among them long enough now to perfect her schoolgirl French and she understood the spattering of rumor and fear. They’ve broken through the line. The Boches are through at Sedan. The army is in retreat—

The news from the Front had blown through the city like a boiling wind. A whisper on the northern outskirts. The report of a friend of a friend. The streets were blazing with half-truths and exaggeration under the deep blue dusk of the shaded lights, and most people were milling south. Sally pushed north, toward the Right Bank and the exquisite little flat fronting on the Louvre. Philip Stilwell’s place.

He had left her waiting at a table with a splendid view of Notre-Dame, conspicuously alone at La Tour d’Argent, not her favorite restaurant in Paris but certainly the most expensive. It was unusual for a woman to arrive without an escort but Gaston Masson, La Tour’s manager, was accustomed to the peculiarities of Americans. If the rest of his diners chose to speculate on the cost of Sally’s dress, her probable immorality, her purpose in waiting nearly an hour for a man who never showed up—she was at least decorative, and hence valuable against the backdrop of the Seine. Her face, with its high cheekbones and too-wide smile, was said to be famous. She was freakishly tall. She carried a gas-mask case instead of a purse and wore last year’s Schiaparelli—an economical gesture in time of war. Shocking pink silk, embroidered with acid green bugs.

“Perhaps M. Stilwell is delayed,” Masson observed apologetically. “If the Germans have broken our line…if they have crossed the Meuse and even now are on the march through Belgium…a lawyer might have much to do…”

But not tonight, Sally thought as she picked her way across the ancient bridge. Tonight he was going to ask me to marry him.

The note had come at five o’clock, hand-delivered by one of Sullivan & Cromwell’s messengers because she had no telephone in her flat in the Latin Quarter. Sally dearest I might be a little late for dinner this evening as I’ve an appointment with a member of the firm…Ask Gaston to seat you and order up a bottle of champagn… A lawyer’s wife, she’d thought, would have to adjust to such things. But Philip had never come; and rudeness was unlike him.

At the end of the bridge she hesitated. The darkened bulk of the Louvre loomed on her left. Without its usual blaze of light the city seemed forlorn and spectral, the people muttering through the streets like an army of the dead. Sally heard an air-raid siren shrill, and the high-pitched tinkle of breaking glass. A woman sobbed. Gooseflesh rose along her bare arms and she understood how solitary she was, how vulnerable. She ought to head for a bomb shelter, but nothing had fallen on Paris during the tedious eight months of phony war, so she squared her shoulders and walked toward Philip.

Another woman woul

d have doubted herself. Assumed that he hadn’t shown because he didn’t love her. That simple thought never occurred to Sally. She had mapped Philip’s soul quite thoroughly during the long months of the past winter, her job abruptly over, the whole question of her future hanging in the balance. She knew he’d been worried for weeks, and that it had something to do with S&C—with his work at the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell.

They’d met the previous August, Philip new to Paris and losing his way on the Rue Cambon, searching for S&C’s door and stumbling instead into the House of Chanel, which sat at number 31. Sally had been descending the famous staircase—Coco’s preferred runway—to the admiration of the men and women seated expectantly below. It was Mademoiselle’s fall collection, the last collection she would design for years, as it turned out. Sally had worn one of Coco’s little black dresses, very chic and timeless in the usual manner; it was Chanel who’d made black fashionable when it had always been strictly for mourning. That August the color was disastrous, a presage of Poland’s martyrdom, all diesel fumes and charred steel.

Philip watched the entire show from the doorway, and when approached by one of the vendeuses, stammered something about shopping for his mother. Sally’d agreed to have dinner with him, although she never really ate during the couture season. It was the beginning of an affair that had carried her headlong to this final night, the empty chair across the snowy linen, the curious gaze of the Paris streets. A meeting with a member of the firm, he’d said. And something had gone wrong.

Philip, she thought, fear knifing jaggedly through her. Philip.

She’d hung on all winter and spring in her apartment in the Latin Quarter, believing the news would change—hostilities would end—Hitler would go away. She rehearsed the truths Coco had taught her over the past three years, her inner voice less cultivated and more Western: Raise the waist in front and a girl looks taller. Lower the back, and you hide a drooping ass. Dip the hemline in the rear because it’ll hitch up along the hips. Everything’s in the shoulders. A woman should cross her arms when her measurements are taken: that way she allows for enough give.

Death in the Off-Season

Death in the Off-Season Death in Rough Water

Death in Rough Water The Alibi Club

The Alibi Club Death of a Wharf Rat

Death of a Wharf Rat The Cutout

The Cutout The Secret Agent

The Secret Agent The Cutout cc-1

The Cutout cc-1 Jack 1939

Jack 1939 Death in a Cold Hard Light

Death in a Cold Hard Light Blown

Blown Too Bad to Die

Too Bad to Die